On Not Believing in Socks

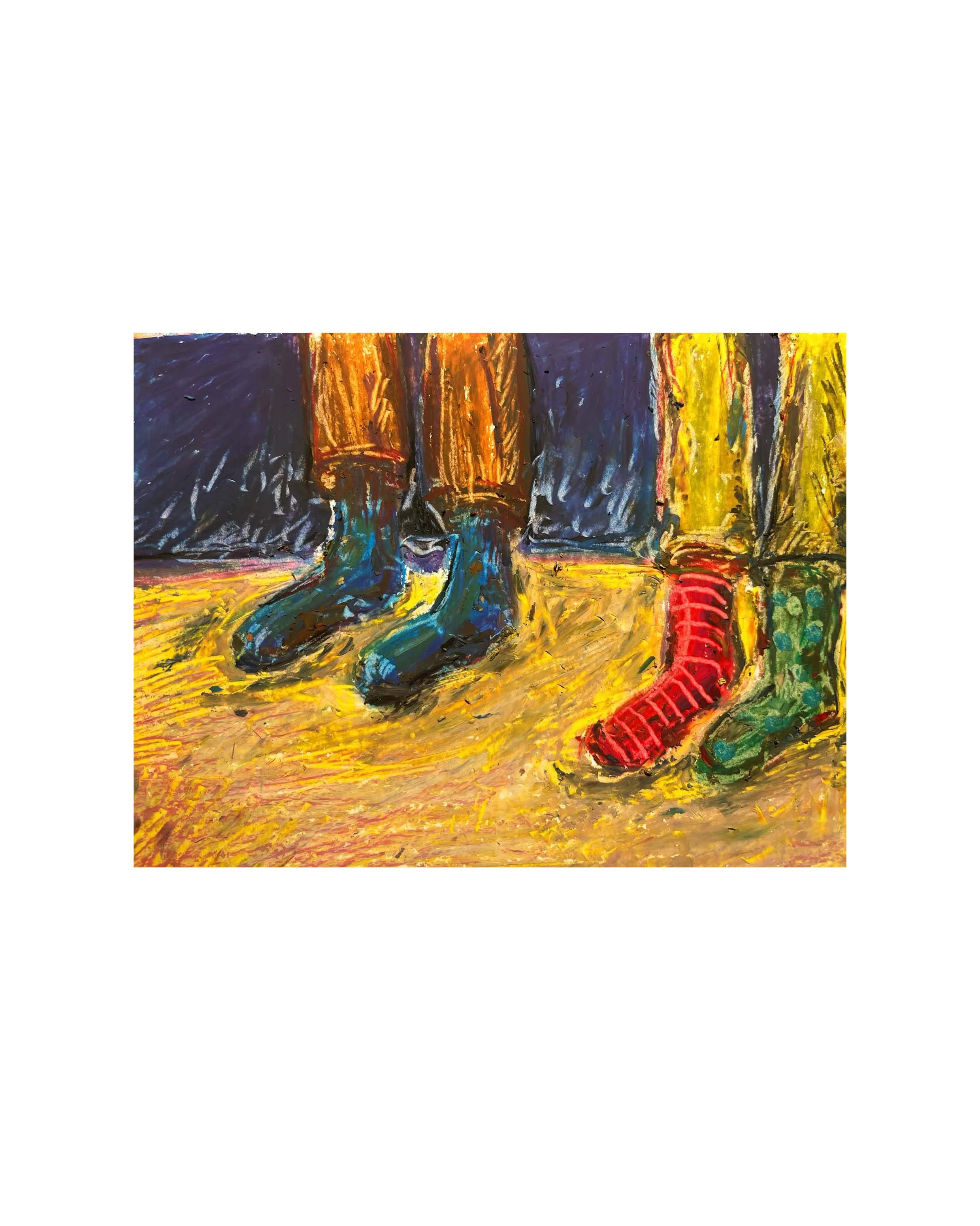

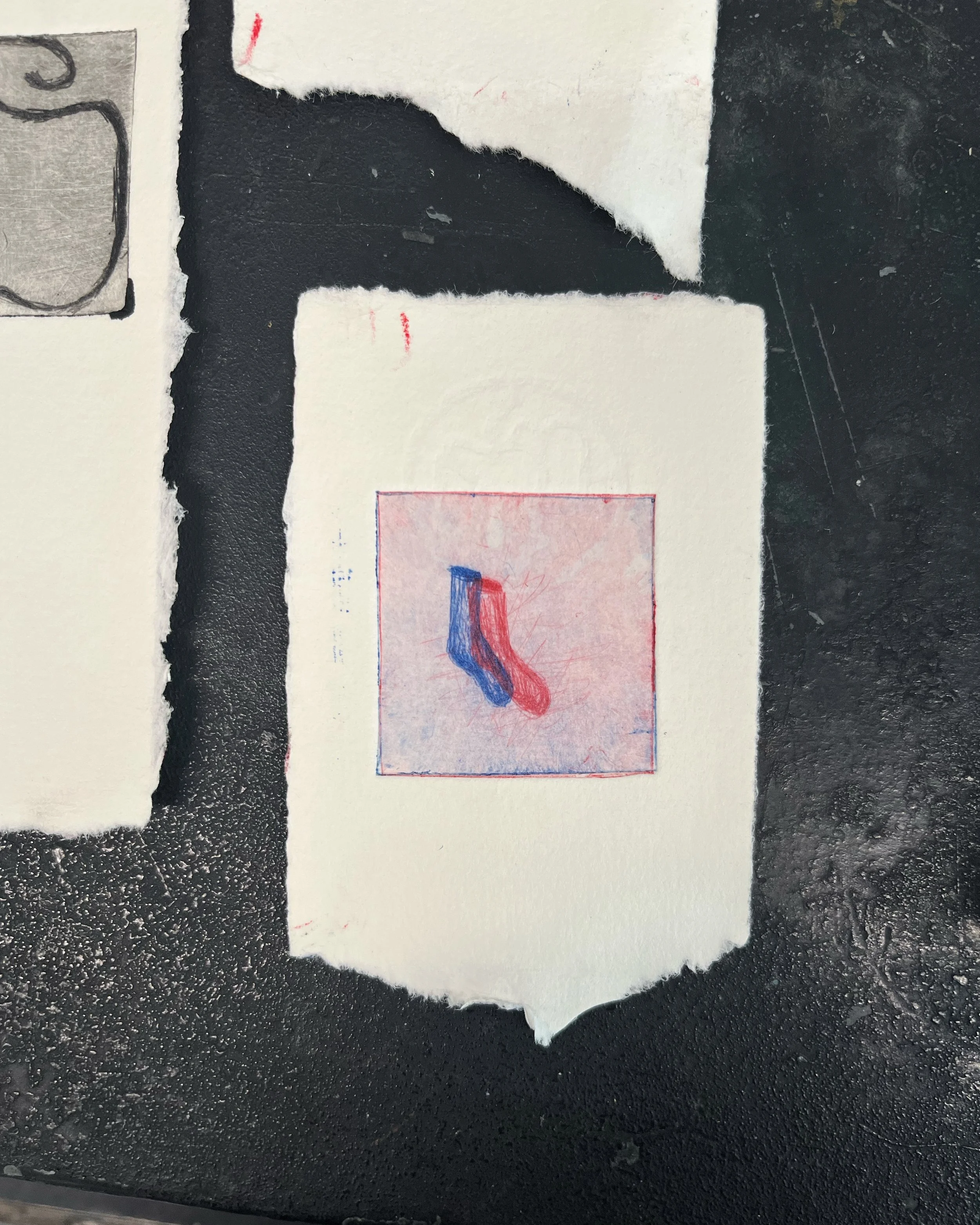

A listener’s question on the radio program Filosofiska rummet (Philosophical room) once asked: Why do socks have to match?

The questioner, Gerd, had grown tired of sorting laundry and of facing the eternal tragedy: the missing sock. As a result, she also had to endure comments in the rooms she moved through wearing mismatched pairs.

Why do we care about Gerd’s socks? The philosophers in the studio offered a surprisingly unanimous answer: convention. Good taste, symmetry, harmony, those things we have historically associated with “the beautiful.” Modernism may have made asymmetry bold, but somewhere along the way the norm persists: two socks should form a pair.

An experiment was mentioned in which artists, art historians, and “ordinary people” were asked to rank images by beauty. Artists and art historians more than often preferred asymmetry. Does that mean artists have better taste? Or, as someone jokingly asked, has their judgment been perverted by a pretentious environment? Tyra posed the question: are mismatched socks a sign of refined aesthetic sensibility, or simply laziness?

The philosophers did agree on one thing: this is about norms we follow, and expect others to do as well. Jonna shared that one of her children feels that the world “holds together”, only if the socks do. As for the other child, she is simply happy if they are wearing socks at all.

And as if that was not enough, philosopher Torbjörn dropped one final philosophical bomb:

A British philosopher, Richard Hare, is said to have claimed that he “does not believe in socks.”

The Sock as a Figure of Thought

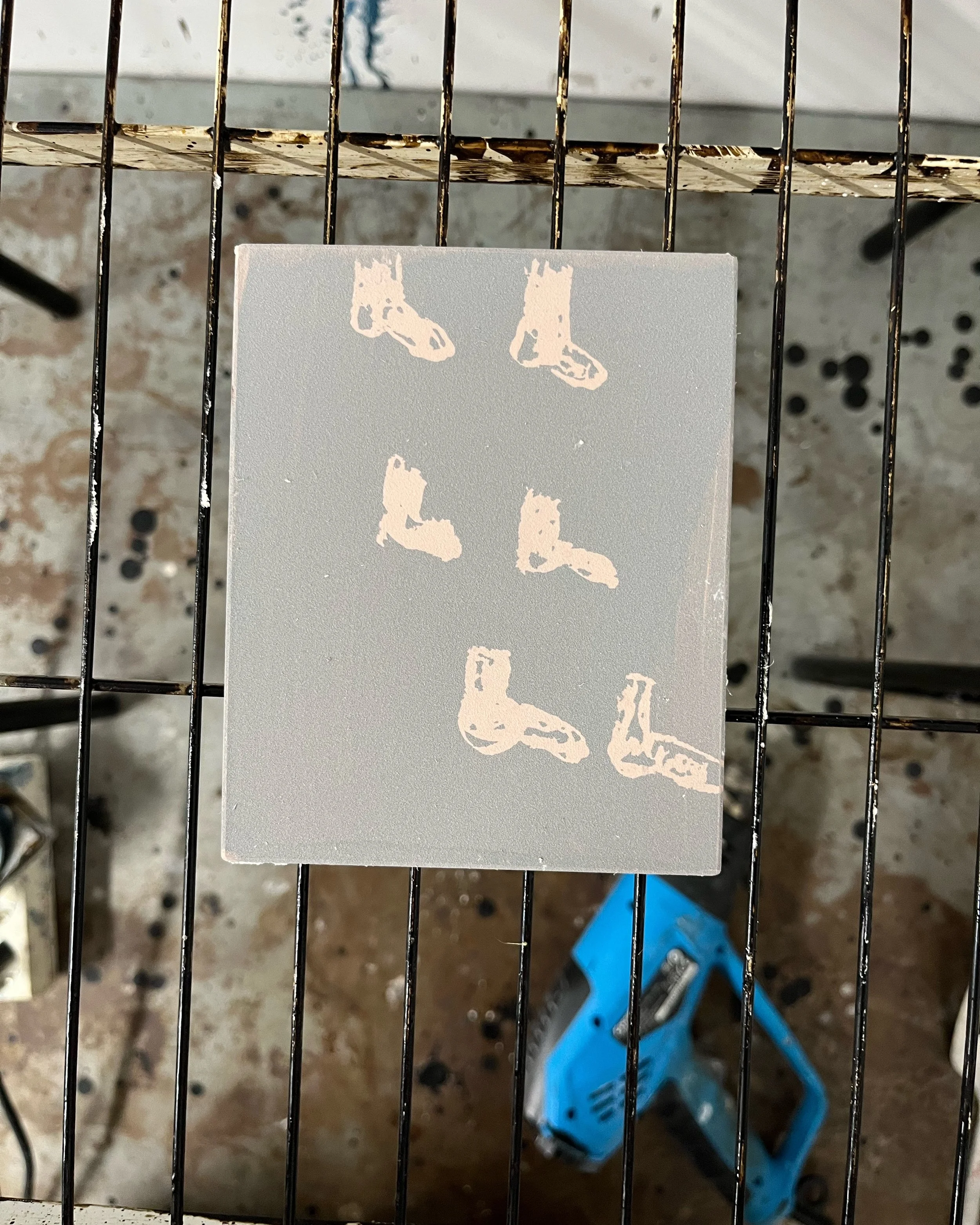

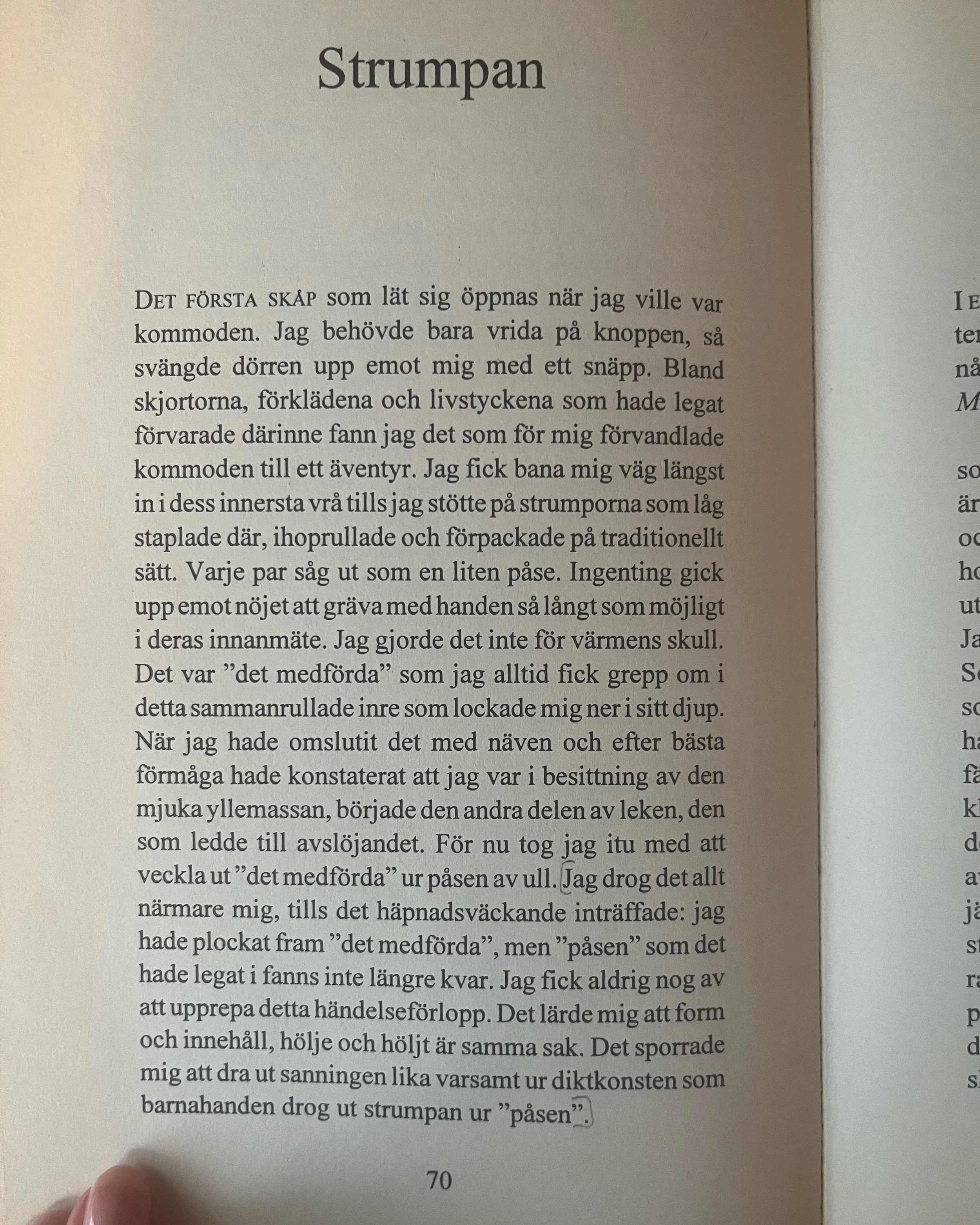

Just when it seemed like everything about socks had already been said, a memory resurfaced in me: Walter Benjamin’s Childhood in Berlin, around 1900. There, he describes how, as a child, he would sit for long stretches turning socks inside out, letting his hand disappear into their crumpled darkness. An everyday fragment that suddenly became a passage into something larger.

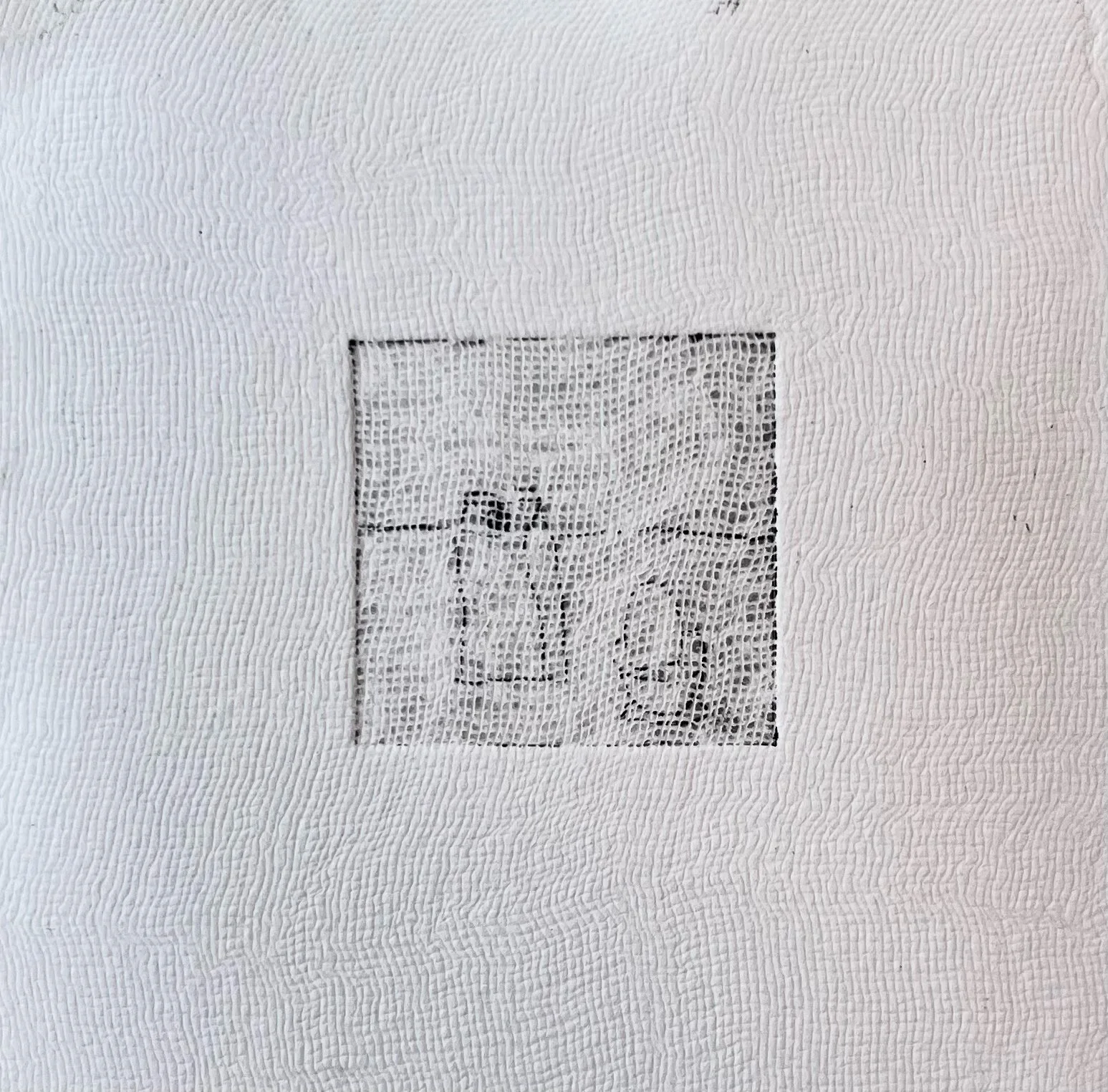

Benjamin writes of das kleine Geschenk, the little gift, something that lay inside the sock, resting in its “pouch,” something that drew him in. When he pulled the gift out to reveal it, he was astonished to find that the “pouch” no longer existed. This taught him that form and content, the veil and what is veiled, are one and the same, and led him to “draw truth from works of literature as cautiously as a child’s hand retrieves the sock from its pocket.”

The sock is an object that moves between body and everyday life, intimate yet unseen. Something we rarely, if ever, regard as an image. But after Hare’s remark, I had little choice but to unravel this banal complexity further.

For Hare, the statement is humorous, but also philosophically sharp. To “not believe in socks” is to point to everything we accept as natural, that is in fact a habit. It exposes how our relationships to objects and to one another are governed by narratives we rarely notice, yet follow daily. The everyday object reveals an entire structure of thought. Hare does not literally mean that socks do not exist. Rather, he uses the sock to show that our relationship to socks says more about human habits, needs for order, and identity projects than about the objects themselves.

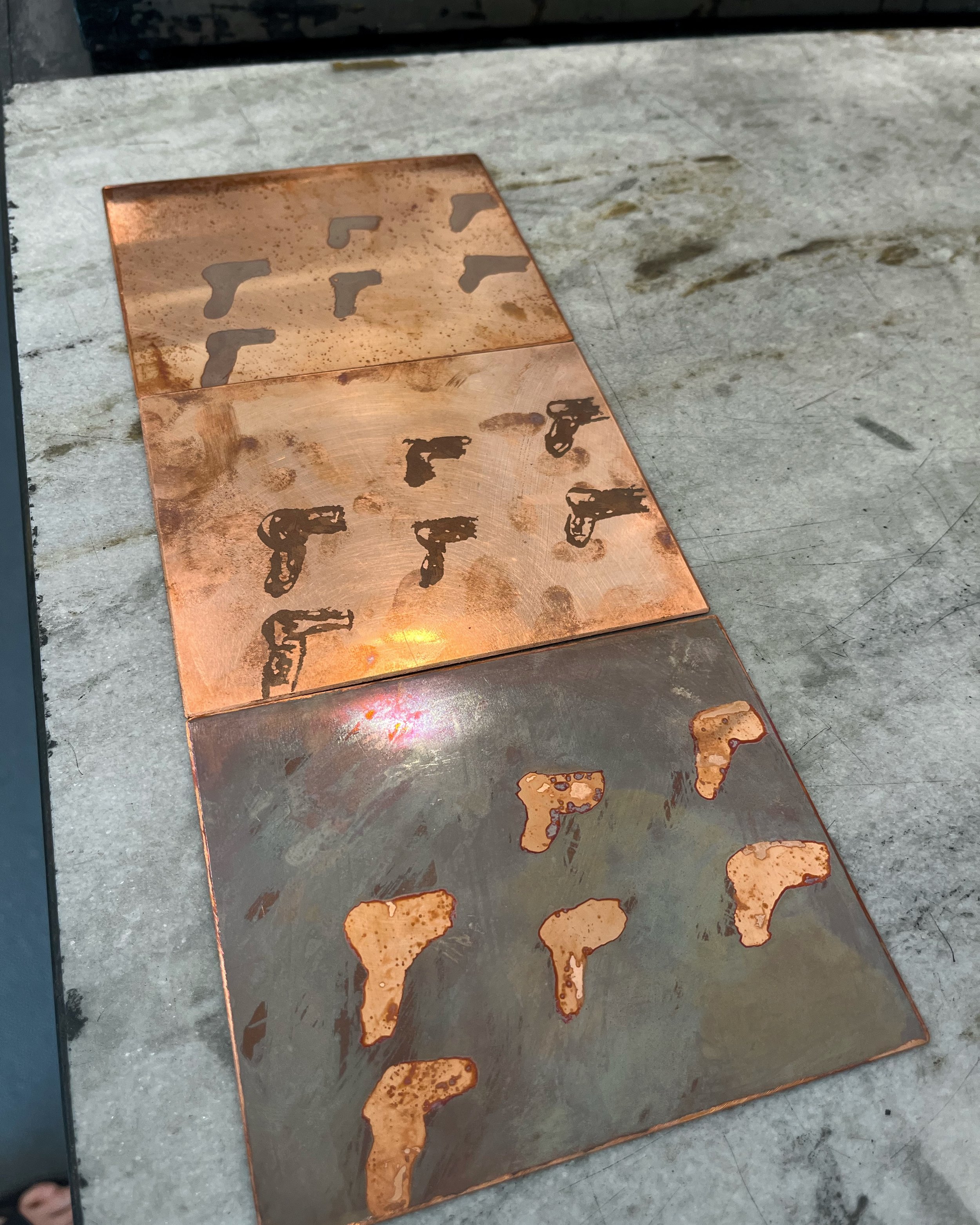

The claim of “not believing in socks” echoes both Hare’s skepticism and Benjamin’s poetics: a mundane artifact that reveals how we assign meaning, how we dismiss, and how we forget to see.

Benjamin approaches the sock from the opposite direction, as a portal. A glove, a button, a child’s toy, any of these could open the archive of memory for him, disrupt the inertia of everyday life, and reveal another form of knowledge. The movement is from play to insight: that surface cannot be separated from depth, and meaning cannot be extracted without damaging form. Truth is not seized, instead it requires a listening touch.

Hare and Benjamin thus move toward the same point from opposite sides. Hare doubts the taken-for-granted nature of objects. Benjamin opens their interior. The sock ends up in the crossfire, both trivial and cosmic. It is an object that only begins to speak once placed within the space of the image.

When Objects Carry Thought

The point is not to observe the sock from a distance and imagine its perspective. That is not quite where I am headed. Rather, it is about what happens when we think through an object. When the hand of thought, like Benjamin’s literal hand, slips into the sock and turns it inside out, a corresponding turn occurs in thinking itself. The sock ceases to be the object of a thought and instead becomes a thought in its own right. In that movement, thinking reveals itself as something malleable, provisional, and everyday, just as twistable as the sock it seeks to understand.

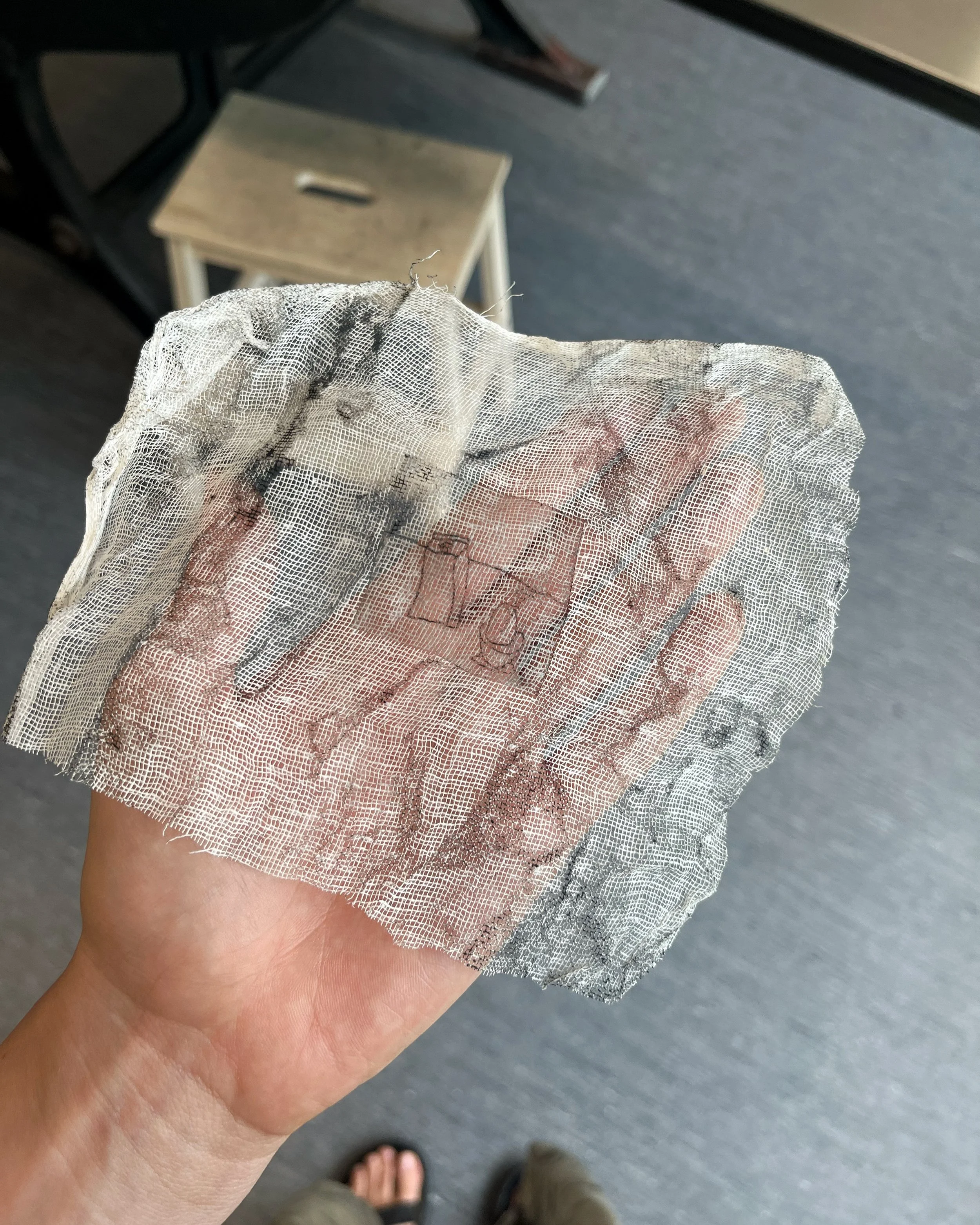

This becomes a method that tests some of our most basic assumptions: that meaning is something we impose on objects; that objects are dead while we are alive; that the world consists of usefulness rather than relationships.

Suddenly, the question is no longer What does the sock mean? but rather:

What does the sock do to me when I regard it as if it carried a trace of thinking?

In relation to other “things” in the world, those we have historically placed beyond our concern, either outside or inside the ethical circle, there is always a certain distance. Think of nature, the milk carton, the egg cup and the egg, the animals that connect them but have also been objectified, reduced to parts of an everyday routine. They exist at a distance we usually approach only through their usefulness and utility.

We tend to grant value to other beings insofar as they resemble us in something we consider “morally relevant.” What humans value in their own lives thus becomes the measure for what is considered valuable in others’ lives. The world is sorted into what has intrinsic value and what does not, as described by Henrik Hallgren, writer and educator in ecopsychology.

This is a tradition of thought that rarely appears head-on; it becomes visible only through a turning. That is why we must continually look at the world’s objects and beings with new eyes, not to determine their place in our systems, but to discover how our relationships to them were formed in the first place.

For Benjamin, the sock becomes a space to think through. Hare’s remark turns the sock into a crack in everyday logic, a philosophical smile. For Benjamin, the sock disrupted the order of the world already in childhood. For Hare, it unsettles what we take for granted in adulthood. For me, it also unsettles the artistic gaze.

In both Benjamin and Hare, the sock becomes a way of thinking about thinking itself. To turn a sock inside out is a micro-resistance to the world as it presents itself.

To let a sock think, or to let ourselves think through it, is to take the materiality of everyday life seriously as a philosophical force. It gives us reason to return to these small (or large) overlooked objects. Not because they carry clear meanings, but because they open spaces where questions of ethics, perception, and relation can emerge. Not in order to draw more figures into an already completed form of thought, but by turning the form itself inside out and revealing the seams in the system, and in ourselves.