Feuilles Rouge – language in friction, resistance in form

For the exhibition Feuilles Rouge at the Printmaking Society, our works gather under a theme where red is not only a color, but also a material. Feuilles rouge means “red leaves” or “red sheets,” but can just as well indicate what binds things together: threads, traces, impressions, and movements that run through both image and action.

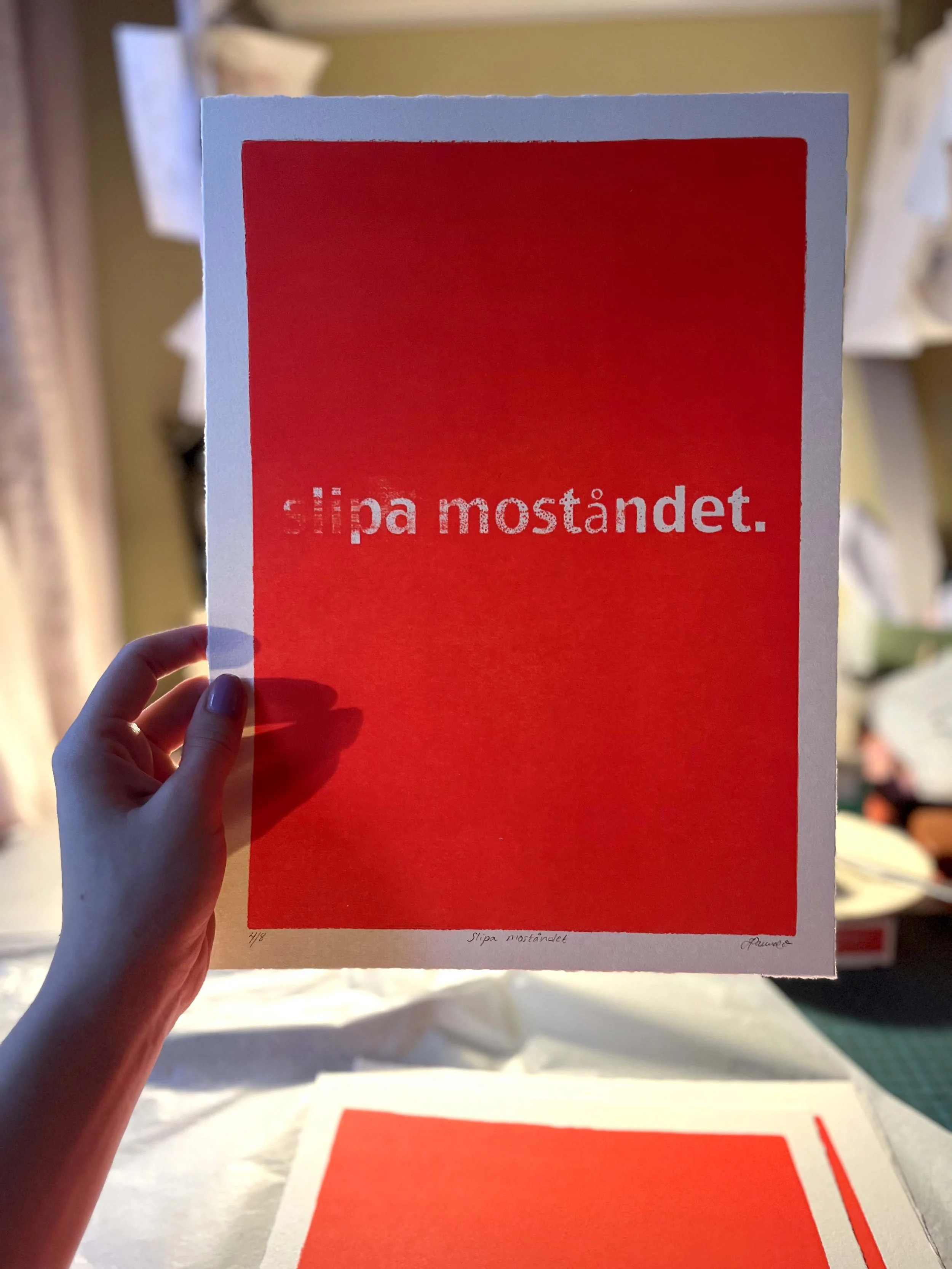

In the work Slipa moståndet, the fracture of language is used as material. The printed sentence contains a deliberate misspelling, shaped by accent and spoken rhythm, opening multiple meanings at once. Between slipa (to sharpen/refine) and slippa (to avoid/get rid of), between friction and release, a space emerges where language carries not only meaning, but also history, relation, and body.

This work was created during my years of study, but for reasons I no longer remember, it never became an edition. When I learned about the exhibition, I retrieved the plate from storage in the basement and printed it anew. It originally grew out of a long email correspondence between me and my father when I moved to Norway and he to Chile. Alongside everyday life and ideas, his Spanish accent appeared clearly in the writing, in a way that closely mirrored the spoken rhythm I grew up with.

Ett öga rött (One Eye Red) by Jonas Hassen Khemiri, is a book about a teenage boy in Stockholm with Moroccan roots, who keeps a diary to strengthen his language and preserve his identity. He struggles against what he calls “the Swedish assimilation process” while navigating life in the suburbs, school, and his changing relationship with his father. I remember reading it and how the language in that book gave me an almost physical joy. The liberated grammar, the direct tone, the playful friction, everything usually kept outside what is considered “correct”, suddenly became literary, possible and alive. Just like in Alejandro Leiva Wengers book Till vår ära (To Our Honor), it felt like seeing a language I already carried through family, but rarely saw allowed into formal text.

The sentence from my father that I chose to print stayed with me as a peculiar question mark. I didn’t fully understand what he meant, and I deliberately avoided asking him. It felt as if the magic would disappear if I tried to pull its logic into the light. What was really happening there? Did he mean that we should avoid resistance, free ourselves from it? Or that we must sharpen resistance; refine it, hone it, become more attentive rather than more frictionless? Was it a call for rest or for action? Perhaps both.

(A brief note for English readers: the printed phrase contains a spelling slip; “slipa moståndet” in my father’s Swedish. The slip creates a double meaning: slipa = sharpen/refine, slippa = avoid/get rid of. The second word “moståndet” is a misspelling of the word “resist”, reading how it would sound in his usual accent.)

I recall studying aesthetic philosophy at Södertörn Univeristy, where we were asked to select a work at The Modern Museum and discuss it through Susan Sontag’s essay Against Interpretation. Sontag insists on art’s right to remain undescribed, not dragged into over-explanation where meaning is flattened rather than opened. The work we chose was a large, pale, pastel-toned, expressionist painting, one of those pieces some dismiss as “childlike.” The more we talked, analyzed, and dissected it, the more its glow seemed to fade. We had, as Sontag might say, talked the spirit out of it. Sometimes ambiguity is the last form of honesty. Sometimes the imagination grows when we let the image remain open.

When language breaks the norm, another kind of presence can appear, something personal, unguarded and true, it basically allows for someone to appear. I could hear my father’s voice in the misspelling, and I could feel my own confusion just as clearly. A voice that breaks is also a voice that carries.

The matrix is a plexi cut with laser cutter, printed as a relief in fluorescent red. In the gap between sharpen- and avoid resistance, (one meaning friction, the other struggle), something human, and perhaps political, takes shape. A wavering language often says more than a marching one.

Today, language is increasingly used as a mechanism of control, a tool to sort, judge, and decide who belongs. Swedish is not my father’s mother tongue, but it has been his language for many years. And the right to speak with an accent, to take part in norm shaping conversations without following the norm’s grammar, is essential to a living society. Cracks are not flaws; they are places where meaning, creativity, and connection form.

In a climate where “Swedishness” is increasingly tied to ideas of purity, correctness, and uniformity, this sentence suggests another movement: that to sharpen means to refine, not erase. To work with resistance, not against it. To let language breathe, tremble and play. Perhaps this is printmaking as listening: an homage to the voices that move in the in-between.

In the end, perhaps the question is whether we continue to choose language in its living sense, the kind that transforms and is allowed to keep transforming. Choosing that is already a form of protest: choosing creation instead of what stiffens and closes.

A protest does not always carry a megaphone, it can just as well carry a brush, a drypoint needle, a digital pen, or a shaky line of words. To keep creating despite worry, to write despite doubt, to print despite the lack of return, this too is resistance. It is caring for a language allowed to err, standing by what doesn’t fit the calculation, and making room for what cannot be explained, only shown.

But perhaps it is time to use our protest, quietly or loudly. Resistance does not always need to rise in volume. Sometimes it is sharpened, letter by letter, until something begins to shine through.