The Shadow of the Wind – When Books Move and Time Is Hidden in Chile

On the evening of April 25, in 1974, just after eight o’clock, my father returns to his street on Plaza Mori in Providencia. There he encounters men in civilian clothes asking for an address, an address he would rather not reveal. Instead, he points toward the street sign at the corner, as if it might answer on his behalf, and then hurries on toward his apartment.

At that time, he used to meet around ten leaders a week at carefully chosen contact points. Between these points, money and information were circulated within the resistance movement. The locations were changed regularly, had an expiration date, and were designed to reduce the risk of anyone falling. For those who did fall, at least twenty-four hours of torture awaited, an intense attempt to make time speak.

That evening, a burning urgency rises in him, the money he is responsible for must be hidden. On the bookshelf you find classics, poetry, philosophy, and drama. He opens their spines and slips money between pages. Roughly twenty books together form a temporary cash vault.

The next day, he falls.

But they never find the money.

The military does not even glance at the bookshelf. They do not look at the gold-lettered spines or the classics. The books stand there like furniture, like something harmless. The money exists like ghosts, invisible, as if it had been placed under a spell by the words and titles surrounding it.

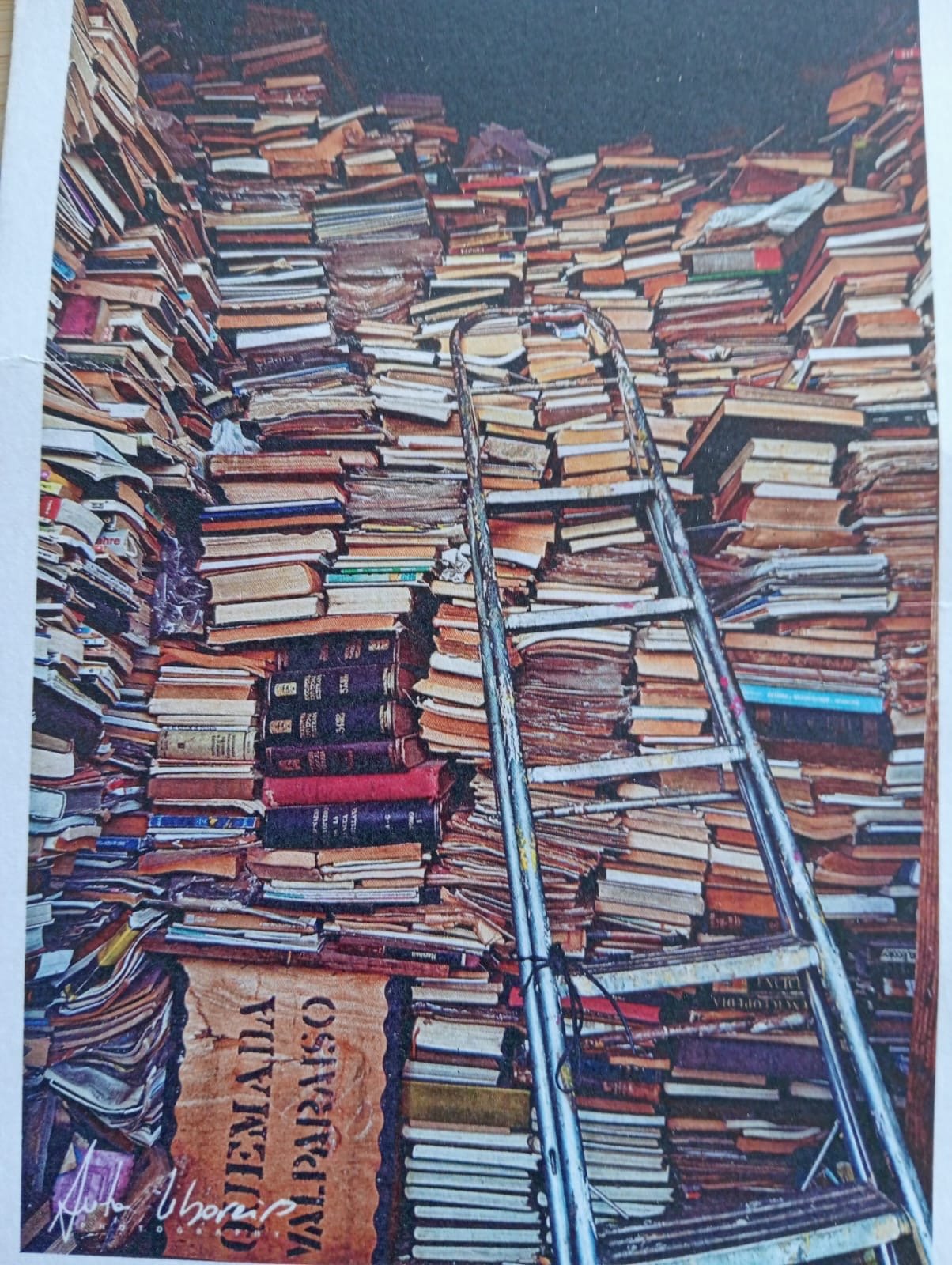

When I traveled to Barcelona this January, I brought The Shadow of the Wind by Zafón with me. Despite its weight, I wanted it as a kind of spiritual compass, something to guide me through the city. The novel tells the story of Daniel, a boy in Barcelona whose life is transformed the day he finds a book in the “Cemetery of Forgotten Books”, a labyrinthine archive of discarded stories.

In Zafón’s world, Barcelona itself becomes a labyrinth. The books are as enigmatic as the Gothic quarters. Daniel is followed by a shadow, and a sense of threat hovers over him. There is a man who burns books. When Daniel encounters him, he is described as shriveled, his skin seemingly drawn tight by heat. He smells of ash, as if book burning were not merely an act, but something that had entered his body. A human being who has become a trace of what he does.

It was through books that my father and his comrades learned how to move information in secret. He had also memorized poems, poems whose exact length he knew. Under torture, they became a clock with walls. While interrogators tried to distort time and make it dissolve, the poem ticked inside him. Information could be revealed precisely when it was already too late.

Literature functioned both as escape and as manual. A way of responding without words. Silent, inward, and impossible to confiscate.

At one point, he is allowed to meet his mother and sister. He manages to tell them that they must take the books from his apartment. Because there, between the pages, lay what determined the difference between survival and loss.

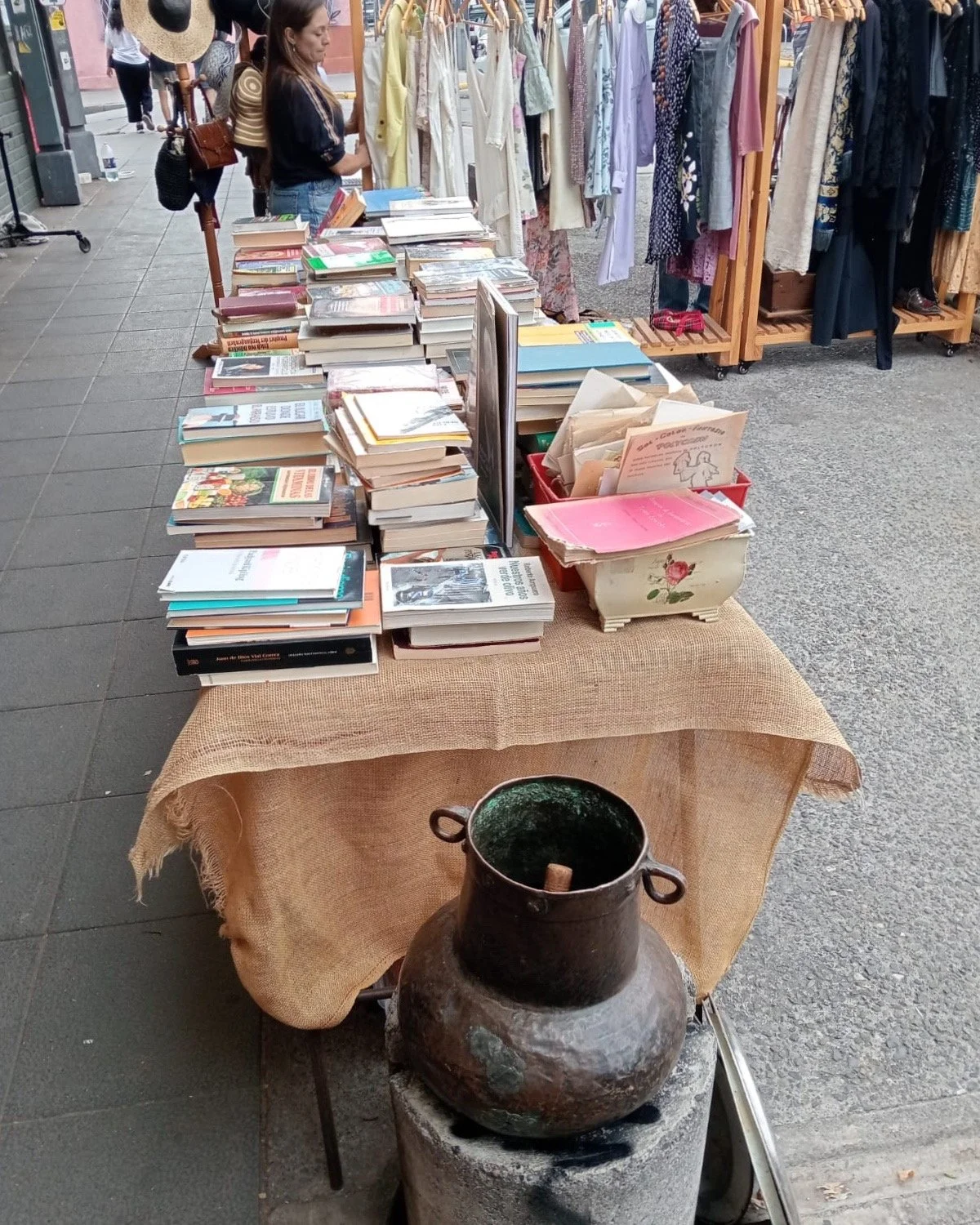

In Santiago today, booksellers line the streets. The books come from homes that have been emptied, from people who have moved, disappeared, or been unable to take them along. Books no one really wants. They are stored in an unappealing heap in a storage room before ending up on a table on the street, in the hope that the wind might catch a curious soul, lift the veil from a book’s face, and break the spell.

In 2024, the international section of Stockholm’s City Library was dismantled. It was not profitable. The books were borrowed too little and took up too much space. So they were moved. Some disappeared. One can wonder which languages vanished first, and which stories became unprofitable. Books often survive by being underestimated, by standing quietly and waiting. But that is also why they disappear.

On December 14, 2025, José Antonio Kast was declared the winner of the Chilean presidential election, a man who openly praised the dictator Pinochet.

In October that same year, my father and I stood outside the Stockholm Concert Hall waiting for documents from a comrade who was to accompany him back to Chile. Papers traveling between different sides of the globe, protected by a plastic sleeve. Application documents to initiate yet another process seeking compensation for the violence the state inflicted upon its citizens.

Justice has not yet arrived.

“The bombs fall closer,” my father often says, when age begins to make itself known and people around him disappear. They die or fall ill. Sometimes they are taken by dementia, a disease that conceals the person inside the body, where memory withdraws before life has ended. Many have settled for small sums of money. Others never managed to submit their papers.

The bodies still remember what happened to them. But in a kind of collective amnesia, the people chose something extreme. Memory seems to have moved elsewhere.

We do not lose memory.

We leave it behind.

Perhaps the rift appears there, between the body that remembers and a society that moves forward as if memory were optional. Perhaps it is not a sudden fall, but a slow drift. Like when languages disappear from shelves. When stories become too heavy to carry in everyday life and are therefore left in a storage. Like when someone says: we don’t want to take the books with us anymore.

When Daniel realizes that his book is in danger, he hides it among other books. He pushes it in between Victor Hugo, Moratín’s comedies, philosophy and poetry, and titles he can barely pronounce. Hidden within the body of literature, amid the noise of other lives. There are so many books that drown in oblivion, Daniel says. The outside world becomes forgetful, and the more it forgets, the more it seems to believe itself to be free.

Forgetting is not merely an accident. It is also a strategy. And every book that remains, every book that happens to fall into the right hands, is a small disruption in that self-deception.

Zafón writes about books as hidden places. Sometimes we hide in books. Sometimes the book hides us. A poem can be exactly long enough for time to take form again. The book becomes camouflage, invisible to power and therefore both life-threatening and life-saving.

In The Shadow of the Wind, Clara’s father says that people never look at themselves in the mirror, especially not in the midst of war. A mirror requires stillness. In war, there is only forward motion, and self-reflection is postponed. Books, on the other hand, remain in the hall of mirrors. They carry the side stories and what was left unsaid, what could not be understood when it happened. That is why they become dangerous. That is also why they are sorted out.

“The body learns to take care of itself when one is forced to leave it,” my father writes. It develops its own strategies. Under torture, he could leave his body as if in a dream. His consciousness flew elsewhere, to Curicó, to the poems. It was like that for four months, with brief pauses for sleep. A few hours at a time stretched out on a blue rubber mat.

Violence rarely ends. It continues through fear, shame, and silence. Through new actions. Through the movement of papers and the waiting, violence becomes bureaucratic and drawn out, almost absurd.

Ghosts arise when something has not been acknowledged. When something has not been buried, has not received justice, has not been given language. A ghost can also become resistance, something that returns to say: you were never finished with me.

A clock with walls does not measure how much time passes.

It measures how long you can keep yourself within time.

Time becomes architecture.

The verse, a spine.

The winds that blew through Barcelona carried salt. They moved through the Gothic quarters and opened rooms that were never meant to be closed. In the Sagrada Familia, I was struck by the light falling through the stained glass, like candy for the eyes. The church was built like an instrument, the space shaped for how music would move, bounce, and travel between the walls. Looking up felt like being inside a wind instrument.

That hollowness made me think of Neruda’s poem from the collection España en el corazón. About the Spanish Civil War, addressed to the generals who initiated the war and paved the way for Franco’s dictatorship. A line that reads: but from every hole in Spain, Spain comes out.

The landscape that emerges between injustice and the imagination of something else is as difficult to navigate as the city’s labyrinths. One gets lost, yet is drawn into the rooms that open. The gaze is allowed to wander, linger, and disappear for a while. It is a landscape that inhales the soot of the past and, in its exhale, sketches something new.

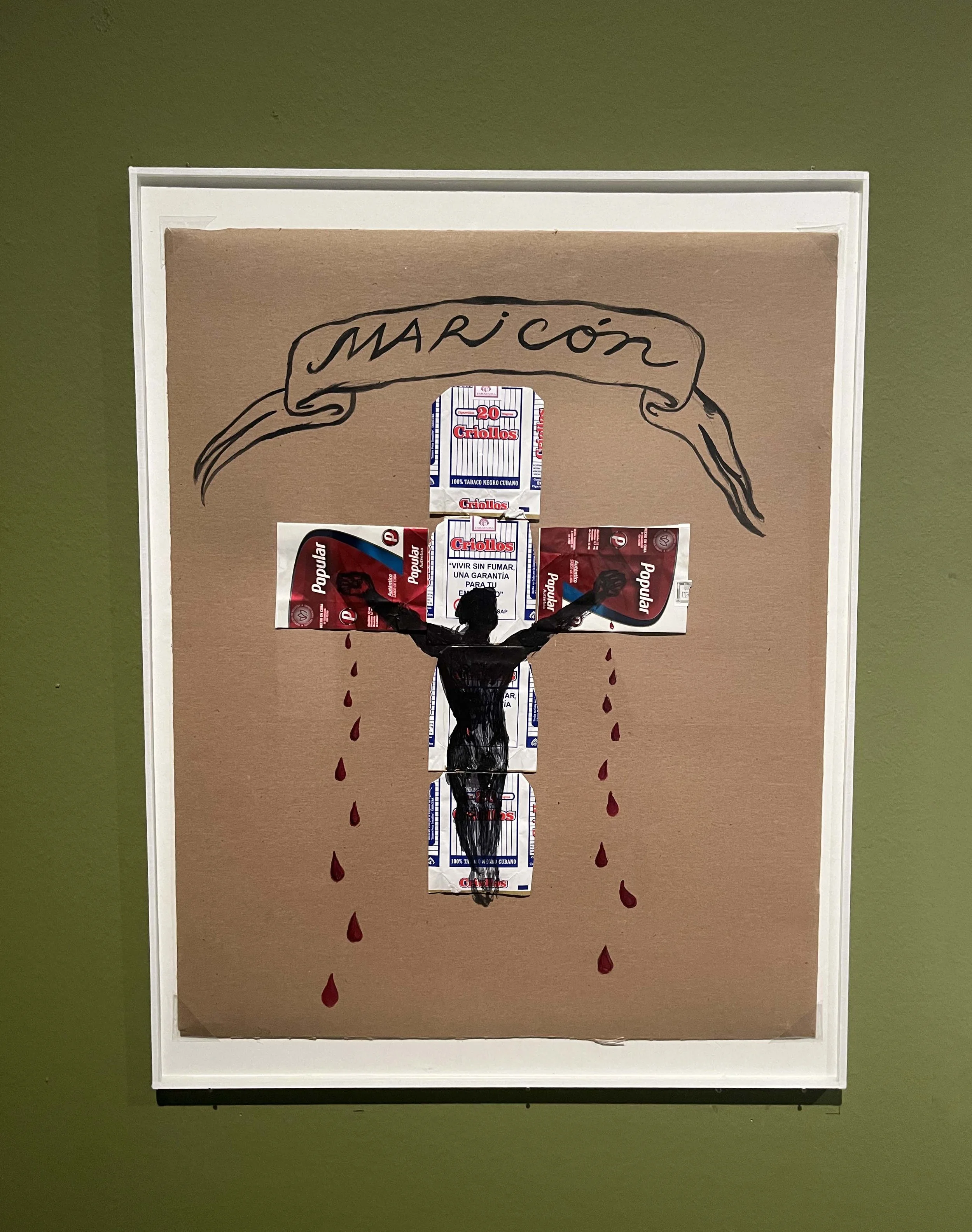

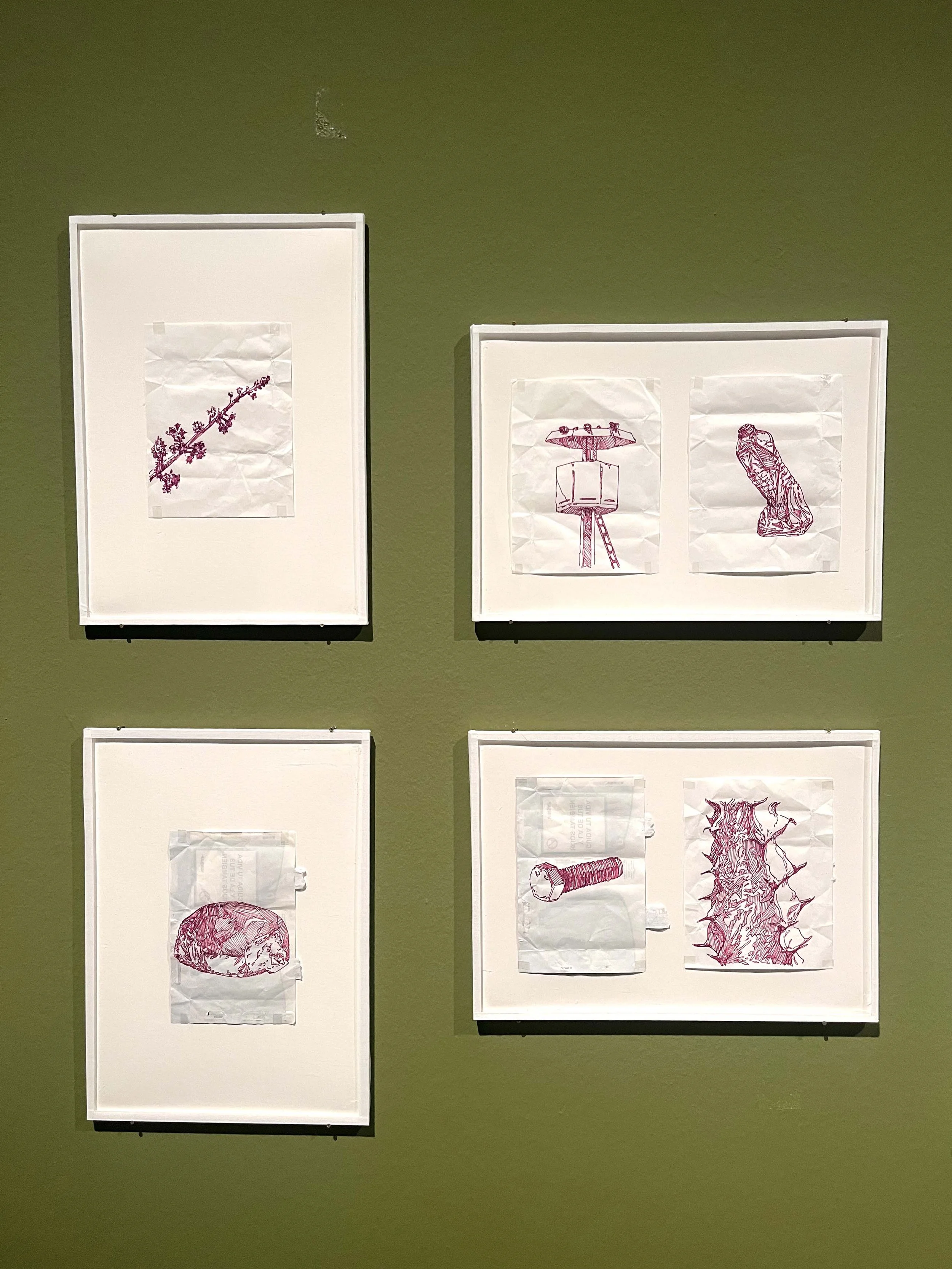

At the Museum of Contemporary Art in Barcelona, I encountered art that sought to carry violence without explaining it. In a project about the imprisoned artist and activist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, his drawings from captivity were recreated, described over the phone, then interpreted by other artists. Drawn with materials that had been available to him: ballpoint pens, the backs of cigarette boxes, fragments. When paper did not exist, the image still emerged. When the body was confined, the line continued to move.

Daniel learns that the author of his book, Julián, is drawn to art, music, and “everything else that lacked future prospects in society,” as his violent hatmaker of a father described it. It is a description of how violence organizes the world early on, not only through blows, but by deciding what is considered valuable and what is not.

The power of literature does not always lie in what it says, but in what it allows us to preserve: money, time, memory. The Shadow of the Wind is not only a story, it is also a condition. When books move, when time is hidden, and when memory changes form in order to survive. A form of resistance that quietly refuses to disappear.