Thoughts from a Cabin - on roach fish and how images re-tune the world

In Dalarna in Sweden, by a small cabin, I observe the movements of the lake water, on the surface and beneath it. People often speak of going to the countryside to find the silence the city lacks. But the silence here isn’t empty, it carries sound, and the space to sketch a new kind of togetherness with what resonates.

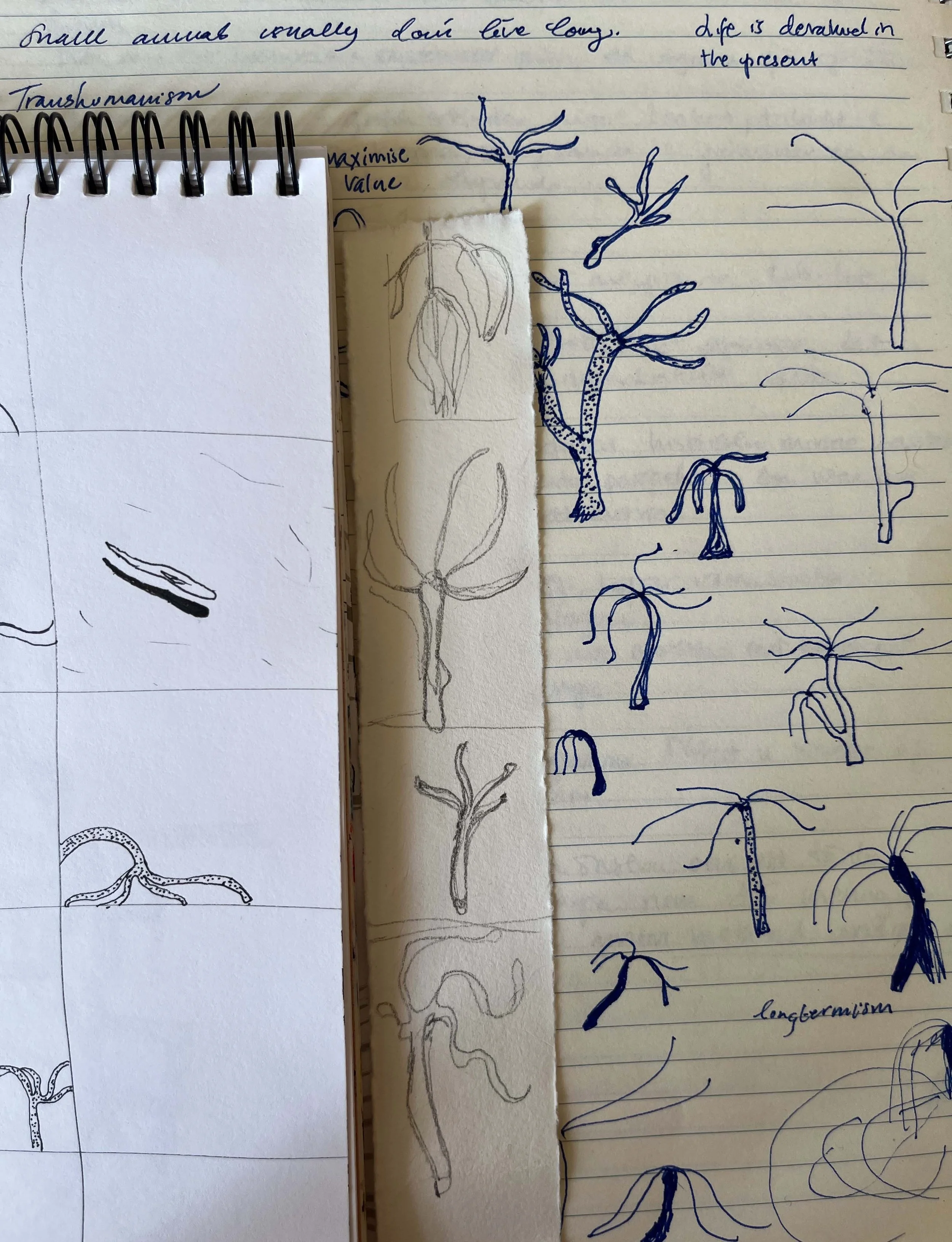

I'm reading De levande (The living) by the swedish philosopher Jonna Bornemark, the first book in her series Vrida världen (Tilting the World). From time to time, I pause to draw: roaches, hydras, small bodies in motion.

Here, we are teased by flies and horseflies. Each day, they seem more aware of our presence. I’m bitten repeatedly, and by evening, one toe swells enough to make me limp. In the woods, fresh elk droppings appear where there were none the day before.

Without TV or city noise, life here feels anything but still. The water is clear, yet I hesitate to let my feet touch the soft lake bottom. I swim quickly past the arms of the water lilies that seem to want to grab me. Smilla licks the stones, as if they taste of something new. Birds dart past, dragonflies hang in the air. Something splashes. Maybe fish. Maybe something else. The left side of my body is sunburnt.

Bornemark writes about being shaped in relation, not through dominance or distance, but through listening. It reminds me of drawing, of trying to approach something without needing to own it. To share space with another life, even if it’s only the memory of it.

When the image is freed from the demand to represent the world as we know it, it can instead offer another rhythm, another gaze. A chance to change our relation to what is otherwise taken for granted. Perhaps this is where the image holds its power, not as evidence or message, but as something that tilts the real slightly. That opens the possibility of something holding more than its function.

Bornemark speaks of regarding the living as melody rather than as mechanism. As nothing for us to solve or master, but to move with, attuned. I wonder if images can offer something similar: not clarity, but resonance.

The roaches won’t let themselves be drawn. I think about how humans usually approach them, by hooking them, removing them from their element, categorizing and studying as if that were enough to understand. Across the water, I try to catch their bodies as they swim toward the shore. They approach, but only if I keep my distance. Their shadows are the clearest part, as if what they are always slips just outside our sight.

In Jonna’s experiment with the roaches, she finds a more “roach-like” way of approaching them. And in doing so, the roaches change, and so does she. When the lake storms, it stirs something in her body too.

Here in the cabin, with her book in my hand and a drawing pad beside me, a slow thought process begins to take form. Listening, anchored in the small:

Can the tactile, the minor, and the body-near aspects of an image create space for what usually escapes attention, and allow for a kind of listening between bodies, memories, and stories?

Bornemark writes: To live is to share life with others. When we draw, print, and linger, we also enter into relation. Not with the world as an object, but as something we live in and with. And perhaps, by allowing our relations to become more attentive, we can begin to change them. Not by forcing the world to speak louder, but by learning to hear it as it is.