The Hydra – a body that changed the world

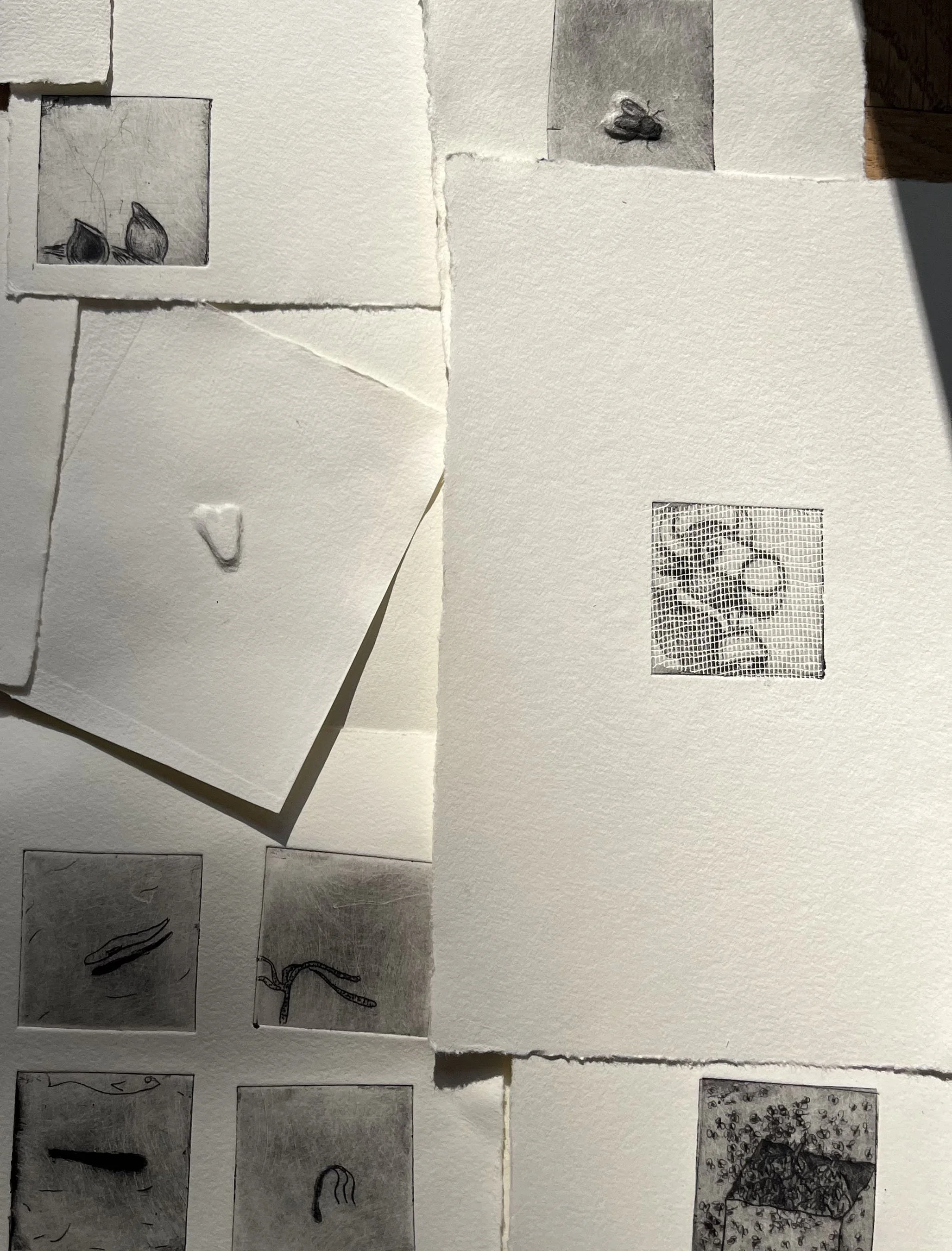

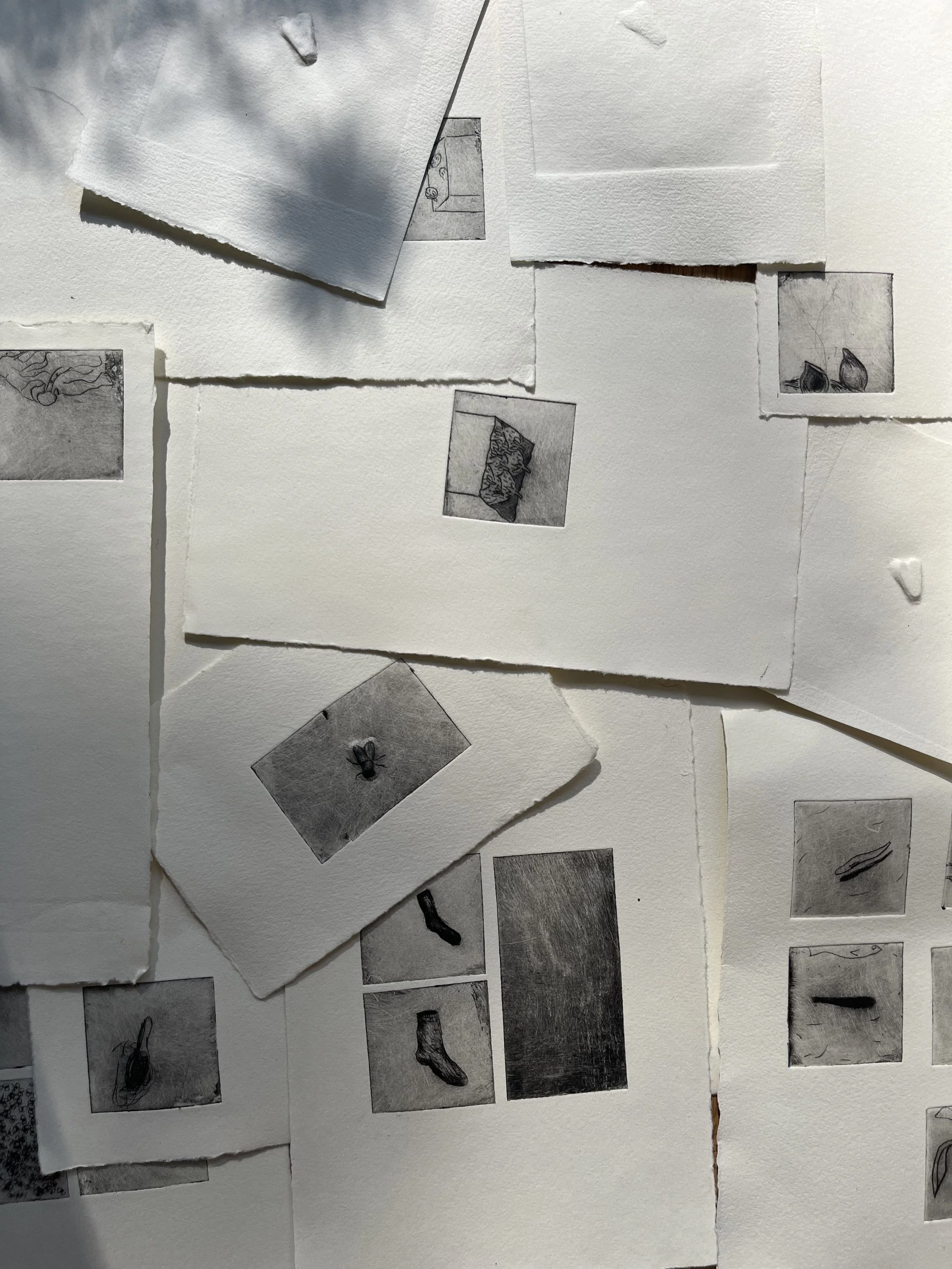

A visual inquiry into microscopic bodies and the objects of everyday life

In the early 18th century, a strange creature was discovered in a still freshwater stream: Hydra vulgaris. It looked like a kind of miniature flower, with tentacles slowly extending into the water. But what first appeared to be a plant soon revealed itself to be able to move, react, hunt, and above all, to regenerate itself. If it was cut into pieces, new hydras would grow from the fragments. It did not die, it divided. It refused to fit into the prevailing categories of life: animal, plant, soul, body.

The discovery of the hydra created both disquiet and fascination. It went against religious and philosophical beliefs about the unity of the soul and mechanistic ideas about the functions of the body. The hydra became an existential problem. How can something be alive without dying in a definitive way? Is it even possible to speak of “one” body, “one” beginning and an end? What does individuality mean when life continues beyond division?

The hydra became an example of nature’s disobedience, questioning a worldview that rested on stable categories.

In my work depicting everyday objects in miniature format, the hydra has entered, perhaps eventually as a motif but at least as a thought that has settled among the others. It does not share their form, but it carries the same gestures: the bodily, the withdrawn, the slowly changing. The hydra carries a resistance to categorisation.

Small as the motifs are, the hope is that they might draw the gaze to what otherwise has no place. In the same way that the hydra once drew eyes to the microscopic, and in doing so altered the view of the living.

It was the Swiss naturalist Abraham Trembley who in the 1740s began to seriously study the hydra. He was based in Haag, employed as a tutor for an aristocratic family. Trembley wrote in his notes about cutting the hydra into parts, sometimes lengthwise, sometimes crosswise, and how each part grew into a new whole creature. It seemed as if life in the hydra had no fixed centre, no soul or core that could be lost. It could reproduce without sex and renew itself endlessly. This challenged the scientific and religious ideas of the time about the structure of life, where each being was assumed to have a unique soul, a centre and a purpose.

For Trembley, the hydra became not only a natural phenomenon but a philosophical challenge. He called it “the immortal animal” and published his findings in 1744 in Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire d’un genre de polypes d’eau douce. The work became a sensation in Europe and was followed by intense debate. Voltaire, Diderot, and even church fathers commented on its existence. How could something so simple be so defiant?

The hydra became a watershed between the Enlightenment’s faith in classification and control, and a growing awareness of nature’s unpredictability. In the history of science, Trembley’s work is considered the beginning of experimental zoology, but it is also the beginning of another kind of thought: that the living does not always allow itself to be classified, and may wish to think with other concepts than the ones we already have.

What happens when a body refuses to have a fixed centre, and what does that do to our worldview?

When Abraham Trembley saw the hydra divide without dying, something began to shift. A new image of the living took form, not as a machine with a beginning and an end, but as a system in constant motion, without a clear core. The hydra blurred the boundary between plant and animal, soul and matter, individual and collective.

Today we live in a time when new shifts are needed, not least in how we understand our place among other species, ecosystems, and technologies. Perhaps we need once again to tilt the world slightly, as Trembley did, in order to listen to what does not fit in. To see the small within the large. To regain reverence for what cannot be measured, classified, or commercialised.

So what happens if we, like Trembley, begin to examine what falls outside, not to capture it, but to let it change us? What does this demand of our gaze, our image, our thought?

Perhaps this is why I am drawn to the hydra today. Not as a scientific curiosity, but as a thought-system in motion. The hydra reminds us that the world cannot always be understood through straight lines and clear centres. It challenges ideas of control, separation, and stability, ideas that still permeate the ways we see, think, and act.

In my artistic practice I have often been drawn to the small and to everyday objects, as carriers of something more than function. Perhaps, like the hydra, they are also difficult to place: they hold memories, bodies, silences, collapses. They are small but charged.

And I wonder:

What is the immortal animal of our time? What is it we have not yet seen, or have not wanted to see, because it does not fit?

Can the image, not as a statement but as movement, be a place where this becomes visible? Can we, through the image’s slow gaze and its resistance to clarity, begin to listen to another rhythm?

Perhaps the immortal animal of our time is not a physical being at all, but a kind of shift in thought. A recurring need to release control. Or perhaps there are still bodies, in water, in soil, in the memories of the body, that carry movements we have not yet learned to listen to.